Sometimes Homeschooling Is Right for One Kid in Your Family and School Is Right for Another One — And Good Homeschooling Is Supporting That

When traditional school is right for one kid and homeschooling works best for another, back-to-school season can look really different. There’s plenty of room for all the options in a happy homeschool life, Carrie discovered.

When I first started homeschooling, I’m pretty sure I believed that homeschooling was all-or-nothing: either you homeschooled your kids throughout their childhoods, or you sent them off to school. But many families I know aren’t like that. Maybe their kids homeschool for most of their childhoods, then head to junior high or high school. Maybe their kids avail themselves of select activities at schools but remain homeschoolers. Maybe some of a family’s kids attend school, while others homeschool.

We’re that kind of family — a part homeschooling, part schooling family. Our 13-year-old son learns at home and has no interest in going to school — ever. Our 10-year-old daughter attends a private, part-time “school for homeschoolers” and says she never wants to go back to full-time homeschooling. It’s a combination that works surprisingly well for our family. You’d never know just how much hand-wringing and agonizing it took to get us to this point.

Our part-time schooling arrangement came about during a particularly long, brutal winter up here in Minnesota in 2013-2014. Cooped up by heavy snow and wind chills that were regularly hitting 20 or 30 below zero, the only learning we seemed to be doing was about working through interpersonal conflict, and boy, was there a lot of that kind of learning. I was stressed. They were stressed. My energy for homeschooling was at an all-time low.

One bitter-cold February day, I sat both kids down in the living room and said I thought we needed to really look at whether homeschooling the way we were was the happiest choice for our family. My daughter, then eight, burst into tears.

“But I don’t want to go to school!” she wailed.

I told her there might be another, less drastic option. A few old homeschooling friends of ours had ended up attending a three-day-a-week Christian Montessori school intended to give homeschoolers some of the benefits of school while allowing time for family learning, too. The school had unusually long breaks — six weeks off in December and January, two weeks in March — and finished for the year in mid-May. There were no grades, no tests, and minimal homework. It felt like School Lite — a gentle way to try out school without completely giving up on homeschooling.

My son was emphatically not interested. My daughter agreed to check it out.

The day we toured the school, I was impressed by the school’s peaceful, friendly atmosphere. But there were also things that gave me pause. The school was run by evangelical Christians, but our family isn’t Christian. Would my daughter be accepted here? Could we as a family feel comfortable here even though we don’t go to church and aren’t believers?

My daughter was quietly observant throughout the school tour, her body language stiff. By the end of the tour, I was sure she was going to say she wasn’t interested. Honestly, I kind of wanted her to say she wasn’t interested. As miserable I’d been with homeschooling that winter, I didn’t feel ready to give it up, either.

As we left the school and walked to our car, I asked my daughter, “So, what did you think?”

“I liked it!” she declared. She was perfectly clear on the matter; she was going to that school that fall.

I wept many tears that spring and summer, agonizing that sending her to school was a big mistake (always out of sight of my daughter, of course).

My daughter did occasionally feel out-of-place attending a school where almost all the other kids were regular churchgoers. She was startled when one teacher mentioned that they didn’t teach about evolution at her school, but that they prayed for people who believed in it. My daughter had taken a class about evolution at our local zoo the year before and had read extensively about it at home. The idea that her school would completely dismiss discussing it floored her.

At home, we talked about approaching these sorts of differences as a chance to learn about the range of perspectives that make up our country and our world and the different ways people approach controversy and disagreement. We brainstormed how she could stay true to herself even if she didn’t feel comfortable speaking up loudly at school. I was grateful that our family’s work together as homeschoolers had laid down a foundation for us to talk this way, and that my daughter’s years as a life learner have given her a strong sense of self she can fall back on when she feels confused or out-of-step with the people around her.

As that first year went on, my daughter found that she really liked the way Montessori learning combines structure with freedom of movement and choice. She’s also fairly introverted, and she found that her school — a school where “nobody knows how to be mean,” as she put it recently — helped her come out of her shell. Seeing the same kids regularly in a routine, predictable environment was more comfortable for her than going to unstructured homeschool play groups, where she’d mostly clung to my side and not talked to the other kids. Once-a-week, short-term classes for homeschoolers also hadn’t really given her enough time to warm up to other kids.

I still don’t believe that school is necessary for kids to get “socialized” — it’s simply that for my individual kid at the developmental stage she was at, this particular school was a better social fit.

Meanwhile, back at home, my son was enjoying having three days a week of one-on-one time with me, combining a few classes at a local homeschooling co-op, a bit of math, lots of reading, and plenty of time pursuing his passionate interest in all things gaming-related. Some days, it felt like we had our own little writer’s colony of two, as my son worked in one room on video game-inspired fan fiction or creating the rules, characters, and storyline for a role-playing game he was designing, and I worked in another room on my own writing. We’d check in with each other over lunch, a board game, or during a hike by the Mississippi, two creative colleagues egging each other on.

My daughter is now preparing for her third year at her school. It will probably be her last one there; she’s feeling ready for a secular learning environment, where she doesn’t worry that she might scandalize a schoolmate if she mentions a pop singer she likes or alienate a teacher if she mentions evolution in a school project.

Luckily for us, there’s another part-time option for schooling here in our town, a public charter school where students attend classes in person three days a week and then work at home two days a week. She is hoping to transfer there for sixth grade. She wants school, yes, but she still wants a bit of freedom about how she spends her days, too.

I tell her that if she’d ever like to return to homeschooling, it’s always an option. She just smiles. “You really want me to come back to homeschooling, don’t you?” she teases me.

Well, yes, I’d love for her to come back to homeschooling. But what I want even more is for her to know she has choices. I’ve learned I can trust her to make the best of whatever situation she’s in and to know what’s right for her, even if it’s not what I would have chosen for her. She’s learned that she can handle new experiences with grace, take the good with the bad, and then walk away when something is no longer working for her. Those are lessons that I think will serve us both well as she moves forward in her life’s adventures, wherever they take her.

How to NOT Teach Your Kids Shakespeare (But Do Something Else Really Important Instead)

Instead of trying to be an authority who has all the answers, I get to learn with my kids and be surprised alongside them. In the process, I get to show my kids what learning looks like, in all its messy glory.

This spring a fellow homeschooling mom I know mentioned a book she was planning to use with her family, Ken Ludwig’s How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare. Ludwig, an award-winning playwright and Shakespeare aficionado, believes that the best way to truly appreciate Shakespeare is to memorize passages from his plays and poetry, so he’s selected a wide range of kid-friendly Shakespeare passages and laid out a step-by-step method for breaking the passages into manageable bits.

As a literature geek, I was immediately salivating at the thought of sharing Shakespeare this way with my son, who’s 13, and my daughter, 10. I knew it might be a stretch for us: my kids tend to be stubborn autodidacts who resist any activity that casts me in a “teacherish” role. But they’ve also enjoyed seeing outdoor Shakespeare performances in our local parks since they were little. I figured they might surprise me and agree that memorizing some Shakespeare together was just the thing our summer needed.

I broached the subject with the kids, pitching it as a way to get in the mood for the Shakespeare performances we’re planning to see this summer. They said “Uh, sure, I guess” in the lukewarm, shifty-eyed way they say yes when they don’t want to rain on my parade but are clearly hoping I’ll forget the whole thing.

Still convinced that they’d get sold on the project once we started rocking our mad Shakespeare skills, I set aside some Shakespeare time on our calendar. Week after week, something always got in the way of us taking a crack at Shakespeare. It was time to face facts: My kids really didn’t want to memorize Shakespeare with me.

I like to make the most efficient use of my mama-energy, and what I’ve found is that I just don’t get a very good return on my effort when I push a project that neither kid is enthusiastic about. On the other hand, I’ve seen many times how powerful the results can be when I back off on my agenda and follow the kids’ interests instead. The learning is deeper and longer-lasting. There’s a flow and an energy that just isn’t there when I force things.

So I put aside my Shakespeare dreams, at least for now, and asked myself the million-dollar question: what had my kids actually been saying they wanted to do this summer? That’s when it struck me: the big thing that my daughter had been saying for months is that she wanted to redecorate her room.

This is a girl who loves design, who constructs dream houses for make-believe clients on Minecraft and revels in mid-century modern consignment stores, a girl who adores thinking about colors and patterns and how they interact. The thought of tackling a room redecorating project intimidated me, but I knew that following through on helping my girl create a new space for herself would mean a lot to her.

Exit, stage right: Shakespeare memorizing scheme. Enter, stage left: room redo.

Together, my daughter and I set a budget for our project. We slapped paint samples on her wall and changed our minds about a half-dozen times (we finally decided on Turquoise Twist, a gorgeous shade reminiscent of a robin’s egg). We checked out online painting tutorials and conferred with the friendly folks at our neighborhood hardware store. We applied painter’s tape to baseboards and wooden trim, sanded rough spots, scraped off remnants of stickers and Scotch tape. We calculated how much paint she’d need to get the job done. And finally — deep breath — we started painting.

Neither of us had ever painted a room before. After swiping a paint roller across her wall for the first time, my daughter frowned and said, “Maybe we should hire someone to do the painting for us. I’m afraid it won’t look good if we do it ourselves.”

I couldn’t help wondering if she might be right, but I assured her that if we followed the painting pointers we’d studied and took our time, we could do a fine job. Maybe not as good as a professional, but good enough. I didn’t want her to miss out on the delicious feeling of competence that comes from trying something you want to do but fear you might not be able to do. (I also wanted to keep her project under-budget.) On this point, unlike memorizing Shakespeare, I was willing to push a little.

We finished the painting a few days ago. It’s not perfect, but the overall effect makes my daughter really, really happy. I think the room means more to her because she was so involved in making it look the way it does. It’s her ideas and work, made tangible.

We’ve spent the last couple of days assembling a storage unit and a desk. There have been many times when we’ve realized we have a part oriented the wrong way and have to remove all our screws and start a step of the process over. We had to problem-solve with her dad when her desk drawers didn’t line up right.

Thinking about all the times that she saw me messing up and starting over during this project, it struck me today that one of the very coolest things about doing this kind of a project with my daughter is that she got to see me being a rank beginner. She watched me looking up answers when I needed them and asking for help when I hit dead ends. She saw how I paced myself to get the job done, taking breaks when I needed them, getting my hands dirty and doing the work alongside her to help turn her daydreams into reality.

In other words, I got to model being a learner right there in front of her eyes. For me, that opportunity to model lifelong learning is one of the most wonderful things about homeschooling. Instead of trying to be an authority who has all the answers, I get to learn with my kids and be surprised alongside them. In the process, I get to show my kids what learning looks like, in all its messy glory. That’s definitely a part of homeschooling I treasure—even if it means I often end up putting aside projects that sound really cool to me in favor of what most interests my kids.

Which brings me back to Shakespeare. If you and your family think Ken Ludwig’s Shakespeare book sounds fun and you decide to memorize some Shakespeare, could you please let me know? I’d love to hear how it goes and find out what you discover along the way!

The Art of Knowing When to Push

How can you tell when your kids need your support for their “no” and when they’d appreciate a gentle nudge?

How do you know when your child wants you to nudge them forward and when they want you to respect their “no?”

One of my guiding principles for homeschooling comes by way of unschooler Sandra Dodd: she says that when kids feel truly free to say, “More, please!” when something interests them and free to say, “No, thanks” when something doesn’t interest them, those kids can’t help but learn, and learn with joy and empowerment.

But what about when my kids say “No” not because they’re not interested, but because they’re afraid? What then?

I recently faced that thorny question while my two kids and I were on a trip to the Florida Keys.

My 11-year-old daughter has long loved the ocean and its creatures. For years, she’s dreamed of snorkeling near coral reefs and seeing colorful tropical fish up close. While we were in Florida, we reserved spots on a snorkeling tour at John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park near Key Largo, the first undersea park in the United States.

A motorized catamaran carried us and about fifty other passengers of all ages to Grecian Rocks Reef, a smooth 30-minute ride southeast of the park visitor center. Our guides were a pair of enthusiastic young women named Brittany and Caitlyn, who proudly informed us they were the park’s only all-female crew.

I was a little nervous as our boat skimmed toward our snorkeling destination, though for my daughter’s sake, I did my best to keep my fears to myself. What would it be like to swim with tropical fish? Would they brush up against me? Would I scratch myself on sharp coral or damage a reef?

When we stopped and anchored near the Grecian Rocks, the other passengers started spraying defogger on their masks, gathering up their fins and snorkels, and heading for the ladders on either side of the boat without any visible trace of nervousness. I asked if my daughter wanted to go in first. She shook her head and said I could go ahead of her.

The water was shockingly cold at first, and I felt awkward in my fins, mask, and snorkel. I also felt vulnerable. I’m used to swimming in pools with sides I can grab on to and shallow ends where I can easily touch the bottom. Now I was treading water in one of the world’s biggest oceans with no land in sight. I felt keenly that I was a land-based creature, an alien here.

I hung on to the bottom of the ladder to wait for my girl to join me. She made it halfway down the ladder and balked.

“I can’t do it!” she whimpered, her eyes wide with terror. “I don’t want to do it!”

My aspiration as a parent is to listen to my kids’ feelings and refrain from trying to talk them out of their emotions, no matter how inconvenient or unwelcome those emotions might be. If they say they’re not ready to try something, I figure they know better than I do what’s right for them in a given moment.

But this time, my intuition told me that my daughter would regret it if she didn’t get in that water. I wasn’t ready to let her off the hook without trying for at least a little while to talk her through her fear.

“It does feel scary at first,” I said, hanging on at the foot of the ladder, still feeling clumsy and a bit scared myself. “But once you get used to it, I’ll bet you’ll really like it.”

I kept trying to pep-talk her, telling her that when we try something that scares us, we become bigger people. We’ve got one less thing to be afraid of and one more memory of tackling a challenge that we can call on for strength later on.

No dice. She was not budging off that ladder.

My son had been less than enthused about this whole snorkeling business to begin with, but there’s nothing like having a younger sibling afraid to try something to motivate an older sibling to dive in and show ‘em how it’s done. He climbed down into the water and flopped in beside me, clearly feeling just as awkward as I did.

Brittany and Caitlyn encouraged my son and me to go ahead and swim around and check things out. They assured me they’d be happy to sit with my daughter while we explored. My daughter said that was all right with her, so my son and I kicked away from the boat.

Only a few yards away from where we were anchored stood clumps of large, boulder-shaped corals swaying with sea fans and covered with forests of staghorn coral, brain coral, and elkhorn coral. Blue tangs, porcupine fish, and stoplight parrotfish nosed peacefully among the corals, oblivious to us humans hovering a few yards above them.

Gradually, I started to relax. The fish were close enough for me to see them well, but not close enough to brush against me. We were at a comfortable distance from the coral, in no danger of touching or damaging it.

Swimming through the silence of the calm, clear water, immersed in a world I’d previously seen only in books and movies, I focused less on how alien I felt and more on how utterly amazing this place was. I bobbed my head above the surface and lifted my mask to see if I could spot my daughter back on the boat. She was sitting in the bow wrapped in a towel, dangling her legs over the side, squinting toward me in the bright sun.

“Let’s go see if she’s ready now,” I told my son, and we headed toward the catamaran.

By the time we’d gotten to the boat, my daughter was standing by the ladder with her wetsuit, snorkel, and mask on, her fins in her hand.

It still wasn’t easy talking her down that ladder. Tears fogged up her mask as she hit the water. Her body was stiff with fear.

With my son on one side of her and me on the other, she took the risk of putting her face in the water. We swam side by side, my son holding her right hand and me holding her left.

Within seconds, I heard her gasping with wonder as she spotted her first fish. Gradually, she grew brave enough to briefly let go of my hand to point at especially big or colorful fish that caught her eye.

By the end of our hour or so of snorkeling, she wasn’t holding my hand at all and was confidently swimming ahead of me. She’d conquered a fear. Her possibilities were just a little bit bigger than they’d been an hour earlier, and she’d fulfilled a dream she’s had since she was tiny.

So how do you answer that question of when to push a child who’s scared to try something? I think for me, the answer comes down to being clear about why I’m pushing. Is it because of some abstract idea about not wanting my child to be a scaredy-cat or a quitter? Or is it because I know deep down, based on my relationship with my child, that they’re more ready than they realize and just need a little encouragement, a gentle little nudge? Do I want my kid to overcome their fear to please me, or because I think overcoming that fear will please them? My answer to those questions makes all the difference.

Riding back to shore with my daughter huddled beside me in a damp beach towel, our minds brimming with the wonders we’d just seen below the waves, I felt confident that at least this time, I’d been right not to take “no” for an answer.

We the People: A Community Model for Exploring the U.S. Constitution

“A Community Conversation to Understand the U.S. Constitution” was a profound and powerful experience for Carrie’s homeschool.

“A Community Conversation to Understand the U.S. Constitution” was a profound and powerful experience for Carrie’s homeschool.

One of the more rewarding learning experiences I’ve had with my 14-year-old son this year has been participating in We the People MN, a series of community teach-ins about the Constitution held at Solomon’s Porch, a Minneapolis gathering space housed in a former church. Run completely by volunteers, We the People MN bills itself as “A Community Conversation to Understand the U.S. Constitution.” I wanted to share a little about our family’s experience with the series in the hope of inspiring other programs like it across the country.

The idea for the series came from Cara Letofsky, a South Minneapolis resident who posted on her neighborhood Facebook group that the 2016 election made her want to learn more about the Constitution. About 60 people responded that they shared that desire to come together as a community to educate themselves politically. A small group of about ten volunteers followed up to plan the series, deciding what amendments they especially wanted to learn about and collaborating to identify community experts who might be willing to tackle leading a discussion of particular amendments. Working their community connections, they lined up a group of highly qualified presenters willing to volunteer their time, including a law professor from a local university, a Minneapolis city council member, attorneys, law students, and organizers from groups that are deeply involved in such contentious Constitutional issues as gun control laws, the right to vote, and reproductive rights.

The organizing committee decided on a format of 10 two-hour presentations, spaced out every two weeks from mid-January 2017 to late April 2017. The first program was a kick-off potluck (because everything always goes better with good food) and a public reading of the entire Constitution, with participants taking turns reading sections aloud at the mic. The organizers also distributed free pocket copies of the Constitution, donated by one of the organizers, Constitutional law professor Matt Filner. Finding free or cheap pocket Constitutions isn’t difficult, luckily. The National Center for Constitutional Studies, for instance, offers a bulk purchase of 100 pocket Constitutions for $40 on their website.

Cara Letofksy, the woman who’d sparked the idea, expected perhaps 20 people to show up to the first presentation. To her surprise, over 80 people attended that first event, and attendance has usually averaged between 100 to 150 participants at subsequent events.

In their initial planning discussions, the organizers knew they couldn’t cover the entire Constitution, so they decided to focus on Constitutional rights that might be most directly challenged under a Trump administration. Other communities might want to choose a different focus, such as looking at ways the Constitution directly impacts local issues and controversies.

The We the People MN series has covered such issues as the branches of government and separation of powers, as well as the First Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of expression and assembly and the Second Amendment’s guarantee of the right to bear arms (as well as the limitations implied by the wording of the amendment). One program was devoted to the right to privacy (and the limits on our privacy). Another event focused on the Fifth, Sixth, and Thirteenth Amendments and their relevance to criminal justice today. The series’ last presentation on the amendments will look at the right to vote guaranteed by the Fifteenth, Nineteenth, and Twenty-Fourth Amendments—and how that right to vote is being steadily eroded today. The series’ last gathering, planned for the 100th day of the Trump administration, will feature a community potluck and “next steps” discussion.

Each event has included a “TED”-style talk by an expert to set the stage for further discussion, followed by time for participants to talk in small groups and share their thoughts and bring up questions for the expert presenter. Almost every presentation has also included brief talks by local activists working in some way on problems raised by ongoing Constitutional debates. Often, these activists have given participants in the programs concrete ideas about how to get involved. For instance, at the event devoted to Second Amendment issues, a presenter from the group Protect Minnesota passed out factsheets about upcoming gun legislation and tips for creating effective talking points. The group highlighted that the most effective advocates usually find a way articulate their personal connections to proposed legislation.

Each presenter also typically sends out readings ahead of time through the We the People MN Facebook page for participants who want to take a deeper dive into topics, though the readings aren’t required to understand the presentations. The readings have ranged from excerpts from the Federalist Papers to summaries of key Supreme Court cases to up-to-the-minute news articles about contemporary Constitutional controversies.

For my son and me, attending these events has been a bonding, highly relevant way to study civics together. Throughout our week, we often find ourselves still talking about what we learned at the most recent We the People presentation. The series has given us new tools for understanding how the Constitution relates to our everyday lives and the lives of those around us.

I’ve also found the series personally helpful as I’ve stepped up my own game as a citizen this year. I’m calling my legislators and attending more public hearings, meetings, and protests than ever (and when I can, hauling my son along with me). Studying the Constitution in this way has given my son and me a clearer sense of what people fighting for change are up against and how we as citizens can make the best use of our time and people power.

Above all, I love that my son has seen people of all ages and backgrounds getting together every other Sunday afternoon to educate ourselves about our Constitution. To me, that’s been such a powerful example of lifelong learning and civic engagement, one I hope will stick with him the rest of his life. I think another crucial piece of the whole experience has been learning from people who are actively involved in the conversation about how to define our Constitutional rights and who are fighting to preserve those rights.

The volunteers who set up We the People MN are hoping to export the model elsewhere. They have plans to create a curriculum to help other people set up their own series, ones that will be relevant to their local communities. If you’d like to learn more, see videos of the presentations, and keep apprised of curriculum developments, you can visit the group’s public Facebook page.

Unit Study Idea: The African-American Struggle for Civil Rights, Past and Present

Carrie’s family wanted to study the history of civil rights in the United States, and they found the project incredibly rewarding. These were some of their favorite resources.

Early this year, I told my thirteen-year-old son I’d like to investigate a historical subject with him over an extended period, to give what we learned time to really sink in. He was game, so I showed him a list of potential topics I wanted to learn more about and asked if any intrigued him. He looked over my list and chose the American civil rights movement.

“It seems especially relevant to what’s going on in the news right now,” he commented. Neither of us had any idea just how relevant the topic was going to be.

The last few weeks have been tumultuous ones in America, with the shootings of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and Charles Kinsey and of police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge sparking grief, outrage, and renewed calls for change. Philando Castile’s death hit particularly close to home for our family; Castile was killed during a traffic stop only three miles north of our St. Paul neighborhood, and several of our friends and neighbors have children who attend the school where Castile worked as a beloved cafeteria supervisor.

The following resources are ones my son and I studied together over the last few months, as well as a few that I’ve found personally helpful. These resources are only a very small sampling of the wealth of materials and perspectives out there, but these resources have given my son and me a historical context about systemic racism and African-American resistance that I just didn’t get from my own school education—or from my life as a white person who’s privileged to ignore racism if I choose. I’ve really needed that historical context these last few weeks. I think everyone does.

BOOKS FOR KIDS AND ADULTS

(roughly for ages 13 and up, though obviously you’re the best judge of what your kids are ready for)

Freedman’s book provides a window into Jim Crow America, detailing opera singer Marian Anderson’s struggle to establish herself as an artist in spite of being rejected by a conservatory based on her race and barred from hotels and restaurants as she toured America. The story continues with her success in Europe, her groundbreaking 1939 performance at the Lincoln Memorial, and the rest of her trailblazing career.

The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights by Steve Sheinkin

Sheinkin tells the amazing true story of black sailors who were barred from combat duty during World War II and assigned to loading munitions at a segregated naval base at Port Chicago, California—without receiving proper training or supervision on safe munition handling. In July 1944, a massive explosion at the base killed 300 sailors. In response to the unsafe conditions and unjustly segregated work environment, 244 sailors refused to go back to work until their grievances were addressed, ultimately leading to fifty of the men being charged with mutiny. Sheinkin takes an in-depth look at this important early case in the fight for civil rights.

“Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King wrote this essay in April 1963 in response to a statement by eight white Alabama clergymen criticizing King’s methods of nonviolent civil disobedience. King’s argument, begun while he was in jail for breaking an injunction against demonstrating, is a powerful defense of breaking unjust laws in order to fight for a higher good, as well as an excellent model of persuasive writing. It’s also helpful for putting current Black Lives Matter protests into historical context; both King and many Black Lives Matter activists argue that in order to get the powerful to come to the table to negotiate, it’s sometimes necessary to break laws and disrupt “business as usual.”

March, Books One and Two by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell

In these graphic-novel style memoirs, Representative John Lewis tells the story of his childhood on an Alabama sharecropping farm and his role in the 1963 March on Washington and the Selma Voting Rights March, among other highlights of a life spent fighting for human rights. Lewis's role in the recent Capitol Hill sitdown strike for gun control makes this an even more timely read.

Marching for Freedom: Walk Together, Children, and Don’t You Grow Weary by Elizabeth Partridge

This account of the 1965 voting rights march from Selma, Alabama begins in compelling fashion: “The first time Joanne Blackmon was arrested, she was just ten years old.” Partridge keeps her focus on ordinary children and teens involved in the historic march and does an excellent job of making the march accessible and understandable for kids. I also love that she shows that there were sometimes disagreements and missteps within the movement; too often, I think we tend to envision the civil rights movement as a perfectly unified, top-down movement led by Martin Luther King. The reality was much messier and more grassroots than the oversimplified version of history enshrined in most school textbooks. This is a great book to read in conjunction with Turning Fifteen on the Road to Freedom by Lynda Blackmon Lowery, a firsthand account by a young person who participated in the Selma March, and We've Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children's March by Cynthia Levinson.

How It Went Down by Kekla Magoon

Kekla Magoon’s young-adult novel tells the story of a black teenaged boy shot by a white man who mistakes him for a dangerous thief and gang member when he’s actually carrying home groceries from the local corner store. Narrated from multiple points of view, the book reveals how painfully difficult it can be to find the truth in the aftermath of a racially charged shooting.

Myers’s 1999 young-adult novel uses an innovative structure — part imaginary screenplay, part diary — to tell the story of Steve Harmon, an African-American teen on trial for murder. Through fragmentary flashbacks, readers gradually piece together Steve’s role in the crime and his journey through a criminal justice system that is predisposed to see a boy who looks like him as a “monster.” For my son and me, this was an eye-opening introduction to the problem of racial bias in our justice system.

X by Ilyasah Shabazz and Kekla Magoon

This fact-based novel by Malcolm X’s daughter and her collaborator Kekla Magoon chronicles the African-American leader’s early struggles with racism as a young boy in Michigan, his years in Boston and Harlem, his imprisonment for burglary, and his subsequent conversion to Islam and decision to change his name from Malcolm Little to Malcolm X.

A FEW MORE BOOKS FOR ADULTS AND OLDER TEENS

Butler’s novel tells the story of Dana, a modern African-American woman transported through time from 1970s America to the antebellum South, where she encounters her ancestors, a white slave owner’s son and his black slave. Through multiple trips spaced over several years, Dana is forced to intervene in her ancestors’ lives in ways that test everything she believes. Butler’s novel is the most compelling, searing examination of slavery and its legacies that I’ve ever encountered, exploring issues of race, sex, family, and gender in mind-blowing ways.

How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America by Kiese Laymon

In this collection of essays, Kiese Laymon examines how racism damages African-American men, and how they in turn inflict pain and damage on themselves and the people they love, especially African-American women. Weaving together hip-hop, stand-up comedy, and other pop culture references, Laymon offers a passionate, introspective, vulnerable perspective on what it’s like to be young, black, Southern, and male in today’s America.

ON THE SCREEN

Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Movement 1954-1985 produced by Henry Hampton :: The first six episodes of this fourteen-hour PBS documentary series cover the civil rights movement from the 1954 Montgomery bus boycott to the signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The next eight episodes focus on such key events as the rise of the Nation of Islam, the Detroit riot of 1967, the Black Panthers, and the clash over Boston school desegregation. The series features riveting, occasionally violent news footage and interviews with people involved on both sides of the movement.

All the Difference directed by Tod Lending :: This PBS documentary follows two low-income African-American young men from the violence-ridden South Side of Chicago who struggle to beat the odds and complete high school and graduate from college. The documentary offers a close-up look at what helped these two students overcome multiple obstacles and setbacks.

IDEAS FOR OTHER RESOURCES

In Memoriam of Philando Castile :: The Minneapolis-based community-building organization Pollen put together this collage of music, spoken word, art, and poetry as a response to the shooting of Philando Castile. Especially noteworthy for homeschoolers might be the list of resources compiled by Twin Cities spoken word artist and community organizer Guante. That list can also be found here: http://www.guante.info/2016/07/a-few-resources-links-and-readings.html

YOUR LOCAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY

One thing I didn’t want to do with my son was pretend that racism and civil rights abuses were only a southern problem. Up here in the Twin Cities, one of our most painful legacies is the fate of St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood, a thriving, vibrant African-American community that officials obliterated to make way for Interstate 94.

The same kind of destruction happened in many other cities, including Chicago, Miami, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Baltimore. The Minnesota Historical Society recently organized a bus and walking tour featuring Rondo history that my son and I were able to participate in. It was a great way for us to learn about the continuing effects of racism and meet people who’d been affected by losing their homes and businesses in the name of progress. A Google search of a phrase such as “How interstates damaged black neighborhoods” yields a plethora of articles. With just a little bit of digging, I suspect you could find similar stories and opportunities for investigation close to home, too—or if you already know about these stories, I’ll bet there are ways you and your family can take an even closer look at the racist legacies in your own back yard and on the roads you travel every day.

Book Review: Bound by Ice: A True North Pole Survival Story

Bound by Ice: A True North Pole Survival Story

by Sandra Neil Wallace and Rich Wallace (Calkins Creek)

Have a kid who enjoys true-life survival stories? Is your family studying polar explorers, post-Civil War America, or the Arctic? This page-turning nonfiction book for ages 10 and up would be a great addition to your reading list.

Award-winning authors Sandra Neil Wallace and Rich Wallace tell the story of U.S. naval officer George Washington De Long’s ill-fated 1879 attempt to reach the North Pole on the U.S.S. Jeannette, exploring what went wrong on the voyage and bringing the ship’s crew to vivid, memorable life. Using the extensive records kept by De Long and other crew members as source material, the Wallaces give readers a close-up look as the Jeannette gets locked in by ice and De Long and his men fight for life through one dramatic setback after another.

One of the things that kept me gobbling up this book were its many surprises. One of the first surprises was learning that in the 19th century, many people believed that there might be a tropical sea at the North Pole. The desire to discover and explore this fabled tropical seascape was part of what drove George W. De Long on his journey.

The book also has an interesting connection to today’s debates over fake news and media sensationalism. One of the funders of the voyage was James George Bennett, Jr., owner of the New York Herald and purveyor of outrageous, sometimes completely fabricated news stories, including an account of escaped zoo animals in New York City goring and mauling people—a completely phony tale. The Herald’s fictionalized accounts of the Jeannette’s voyage misled the crew’s loved ones and fanned wild rumors throughout the two years the crew was out of touch with the rest of the world.

“At a time when science is being increasingly disregarded and disrespected by many policymakers, this book feels like a cautionary tale with startling relevance.”

Another interesting aspect of the Wallaces’ account is the way it demonstrates the danger of making important, life-and-death decisions on the basis of junk science. De Long based much of his planning for his polar voyage on the theories of a so-called North Pole authority who argued that explorers could easily reach the North Pole in two months if they followed a warm Pacific current called the Kuro Siwo. This ill-informed “expert” predicted that explorers would find polar regions “more or less free from ice” and theorized that an expedition could safely complete a North Pole expedition in a couple of months.

At a time when science is being increasingly disregarded and disrespected by many policymakers, this book feels like a cautionary tale with startling relevance.

One of the biggest pleasures of Bound by Ice is the way the Wallaces bring the members of the expedition to life with small, vivid details. We learn that Civil War hero and chief engineer George Melville was annoyed by the ship meteorologist’s tendency to burst into snatches of Gilbert and Sullivan songs. We discover that the ship naturalist was tortured by dreams of pumpkin pie, “the particular weakness of a New England Yankee,” as he put it, when the men’s diets had dwindled down to a monotonous round of canned vegetables and seal and polar bear meat.

Another compelling aspect of the book is the tender love story between De Long and his wife Emma. The authors thread excerpts from De Long’s letters to Emma throughout the adventure, reminding readers of the very personal stakes involved in this real-life drama.

The story of the Jeannette definitely has tragic elements. But it’s also a deeply inspiring story of persistence, teamwork, and devotion to making a contribution to science and history. Readers will come away with a new perspective on the North Pole and a fresh appreciation for the sacrifices that explorers have made to expand our knowledge of the world.

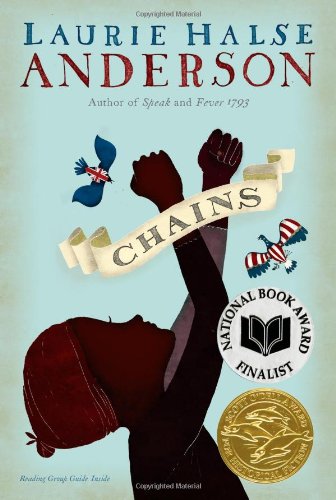

Book Review: Laurie Halse Anderson’s Seeds of America Trilogy

The Seeds of America trilogy looks at the American Revolution through the story of Isabel, Curzon, and Ruth, three young slaves fighting for freedom in the midst of America’s birth pangs

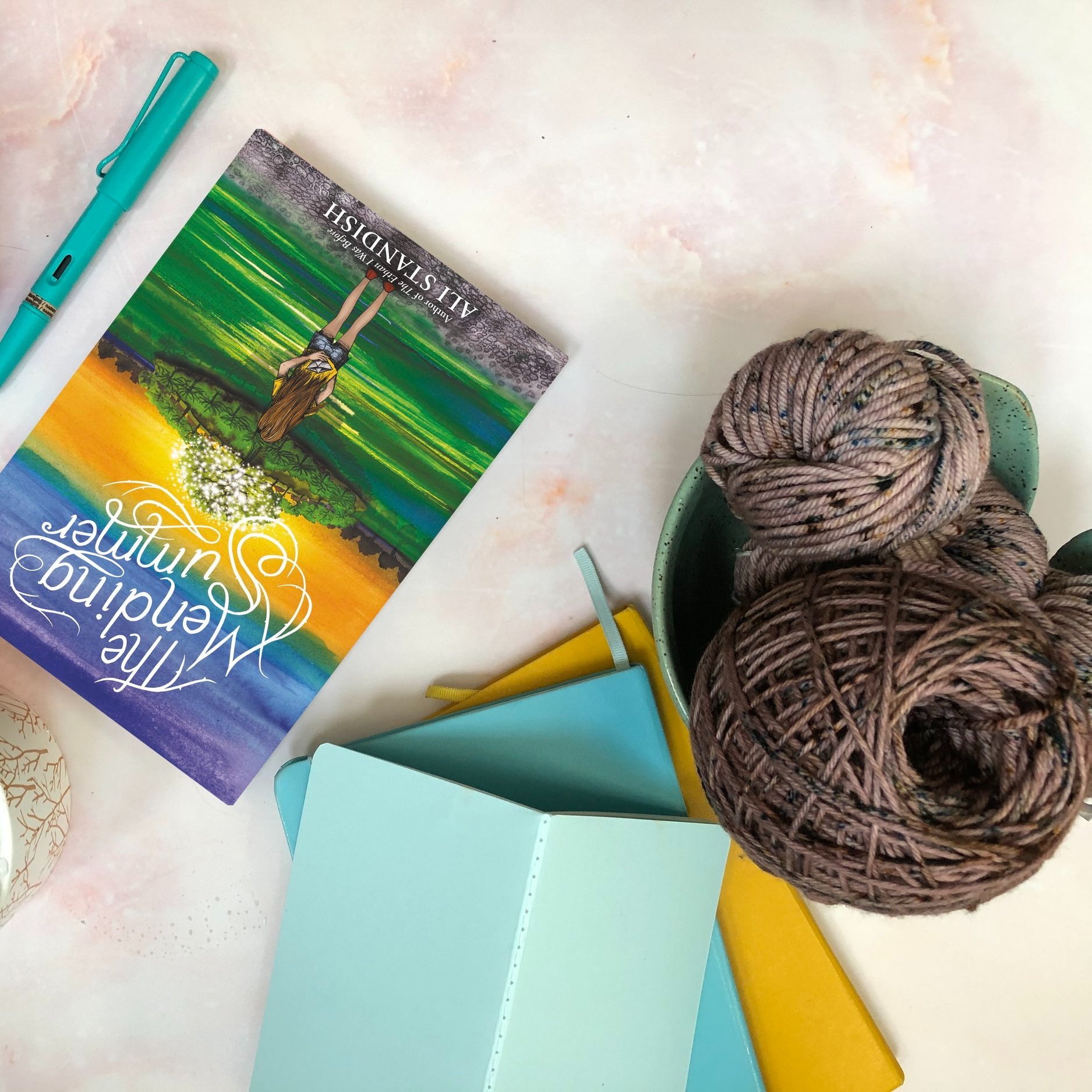

For the last couple of months, my eleven-year-old daughter and I have been devouring Laurie Halse Anderson’s historical fiction trilogy The Seeds of America, which looks at the American Revolution through the story of Isabel, Curzon, and Ruth, three young slaves fighting for freedom in the midst of America’s birth pangs. The series, recommended for readers roughly ages 10-14, opens with Chains, published 2008, continues with Forge, published 2011, and concludes with the long-awaited Ashes, published 2016.

Chains tells the story of 13-year-old slave Isabel and her younger sister Ruth, who have been promised their freedom upon the death of their owner. Instead, they are sold to the Locktons, British loyalists secretly working to undermine the American fight for independence. When the Locktons separate Ruth and Isabel, Isabel is drawn into the American fight for independence by Curzon, a young slave with close connections to the Patriots. He urges Isabel to spy on her owners in the hope that the Patriots will give her her freedom and a chance to reunite with her sister. Isabel ends up feeling caught between two nations, trying to decide which side will give her and her sister the best shot at liberty—the British or the Americans.

Forge continues the story from Curzon’s point-of-view. Curzon, on the run and trying to pass as free after an escape from a fearsome British prison, enlists with the Patriot Army and endures the hardships of winter at Valley Forge. He and Isabel, separated for most of the book, re-encounter each other at Valley Forge and have to sort out their own tangled loyalties and decide the best way to pursue their mutual dream of freedom.

The trilogy’s finale, Ashes, narrates Isabel and Curzon’s efforts to track down Isabel’s sister Ruth while dodging British and Patriot army skirmishes and evading an owner who wants to deprive them of the freedom and self-determination they’ve fought so hard to attain.

As my daughter and have read this trilogy together as a read-aloud, I’ve been powerfully struck by how often Halse Anderson’s trilogy reads like some horrifying dystopia, only to realize that this is, in fact, the story of my own country’s history—just a side of the story that’s long been hidden and ignored. Repeatedly, my daughter and I have found ourselves discussing the ironies of a war for independence that denied freedom to the estimated half-million slaves who lived in the colonies when the revolution broke out. As Abigail Adams wrote in 1774, “It always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me to fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.”

“As my daughter and have read this trilogy together as a read-aloud, I’ve been powerfully struck by how often Halse Anderson’s trilogy reads like some horrifying dystopia, only to realize that this is, in fact, the story of my own country’s history—just a side of the story that’s long been hidden and ignored.”

What makes this fictional story all the more compelling is that Laurie Halse Anderson grounds her creation so firmly in documented history, drawing inspiration from real-life slave narratives and testimony from Revolutionary War soldiers. Halse Anderson titles each chapter with a date, pinning her story to historic incidents in the war, and she also opens each chapter with short excerpts from Revolutionary War-era letters, diaries, newspaper advertisements, and military directives that echo off her fictional narrative in fascinating ways. At times, I’ve found myself wondering out loud about a particularly disturbing detail of slavery or the Revolution that Halse Anderson includes in her story, questioning if something really could have happened the way she describes it, only to have that detail confirmed by one of her historical excerpts.

When I learned about the Revolutionary War as a kid, I learned mostly dates and battles—only the broadest outlines of history—and the focus was almost exclusively on white men’s contributions. I love that this trilogy has given my daughter and me a window into the Revolutionary War experiences of girls and women, indentured servants and slaves, and people of color. It has given us a new perspective on the travails of young prisoners of war and soldiers in battle, as well as giving us a detailed look at the work of maintaining a military encampment and surviving when war made resources extraordinarily scarce. It’s also given us a new appreciation for the contributions that slaves and free black people made to America’s fight for freedom—contributions that often offered them little reward.

Our country is currently engaged in a tumultuous, painful debate about what it means to be a real American and what our country stands for. Laurie Halse Anderson’s Seeds of America Trilogy offers the kind of historical context I think we desperately need in order to see ourselves more clearly, accurately, and truthfully, and to move toward living up to our founding ideals. I’m so grateful to have shared these books with my daughter and to have had the chance to talk them over with her, and I encourage you to check them out, too. Some scenes of graphic violence and injuries do pop up in the books, so you might want to preview before sharing with younger/more sensitive readers. But all in all, I would highly recommend these books, even for readers who don’t normally gravitate toward historical fiction. You’ll emerge from these books with a fresh, unforgettable new perspective.

On Homeschooling and Patience

It happens all the time. I’m chatting with a new acquaintance who either doesn’t have kids or has kids who go to school. I mention that I homeschool. And nine times out of ten, my new acquaintance looks at me with awed disbelief, shakes his or her head, and declares, “I just wouldn’t have the patience for that.”

They’re right that homeschooling has required a lot of patience. But I’m not always sure the kind of patience I’ve needed is the kind of patience they mean.

If they mean that homeschooling must demand the patience to prepare lesson plans and quizzes and sit by my children at the kitchen table to explain and drill until they’ve mastered their multiplication tables or the finer points of diagramming sentences or the names of all the presidents, well, I know a lot of homeschoolers do have that kind of patience, but I’m definitely not one of them.

I don’t prepare lesson plans or give formal lessons. I don’t administer quizzes. I don’t explain things or answer questions in a way that would remotely look like schooling to most people. What I do is explain things and answer questions (and ask plenty of questions, too) in a way that mostly just looks like ordinary conversation. A whole lot of learning happens while my kids, husband, and I are all just talking—at the dinner table, doing the dishes together, on drives, out for a hike, at our local coffee shop.

So I may not have the kind of patience that a lot of people assume a homeschooling parent has to have. But I do agree that homeschooling has demanded that I call on all sorts of reserves of patience I never knew I possessed. So what kind of patience has homeschooling required of me?

For starters, it’s required the patience to wait for my kid to be ready to learn something I think is important for them to learn, instead of forcing them to learn on my timetable. It took a whole lot of patience to back off on pushing phonics readers when my kids were little so they could experience the joy and empowerment of figuring out how to read on their own terms, painlessly, through their love of Garfield and Calvin and Hobbes comics.

Homeschooling, at least the way we do it around here, has required the patience to trust that something that looks like a frivolous pursuit with no discernible academic benefits may actually be a worthwhile endeavor for my kid—maybe because it sparks my son’s imagination, maybe because it gives my daughter a way to figure out some puzzle or question that doesn’t necessarily interest me but is hugely compelling to her. Maybe just because it’s fun. As a homeschooler, I’ve learned to value fun, not just as a tool to make learning more palatable, but as an end in itself.

Homeschooling has required the patience to wait out the long, seemingly fallow periods when not much learning seems to be going on, when our daily routine seems a bit flat and dull, and to trust that if I keep offering my kids new experiences and keep strewing intriguing books and movies in their paths, they will keep learning and growing. It’s required the humility to see that not all the learning experiences in our house have to emanate from me (sigh: what a relief). It’s also required the patience to keep offering new experiences and suggesting cool things we could do or make or try, even if I get turned down again. And again. And again. And. . . You get the idea.

Some kinds of patience come easily to me. I find it relatively easy to be patient when I’m cooking with a child, for example. I’m willing for a cooking project to be slower and messier than usual because it’s so important to me for my child to feel welcome in the kitchen and to have good associations with cooking. I’m easy-going when spills happen, nonchalant about mistakes. It’s harder, for some reason, for me to be patient with setbacks when we’re doing crafts, maybe because deep down, I don’t value making crafts the way I value cooking.

Other kinds of patience are much harder for me, too. When my child gets frustrated over a task and wails, “I just can’t do it” or “It’s too hard,” it’s really, really difficult for me to muster the patience to make space and time for my child’s frustration. All sorts of critical voices harp in my head: He’ll never develop grit if you don’t push him to finish this. . . It’s your fault your kid gets so easily frustrated. . . She’ll never succeed with an attitude like that. . .

It takes a lot of patience, with myself and my child, to slow down and listen to my kids’ frustration and self-doubt without lecturing them about the value of persistence or rushing them to get back to work. Give them time, I have to gently remind myself. Let them express those frustrations and self-doubt. Encourage them to take breaks if they need to, without fearing that they’ll be quitters. Trust.

That word “trust.” It’s such an important one for me as a homeschooler and a parent. As a homeschooler who’s foregoing traditional curricula for the most part (yeah, like a lot of wannabe unschoolers, we use a math curriculum), I sometimes feel quite anxious about the path I’ve chosen. Are we doing enough? (That perpetual question!) Is what we’re doing setting my children up for happy, fulfilling lives?

I recently expressed some of that anxiety to my fourteen-year-old son as we talked about how to approach his high school years.

“It’s hard for me sometimes,” I explained, “not having you follow a prescribed course of study that clearly points to a defined outcome the way traditional high school does. It’s hard to trust that it’ll lead you where you need to go.”

“Yeah,” he said, “but if I spend my time doing things that interest me and that I like, don’t you think that will probably lead me where I need to go?”

Ah. Well, yes. Probably. I think back on all the time I myself wasted as a young person, trying to jump through hoops that adults set up for me, not spending nearly enough time asking, “Hey, wait a minute. How do I want to spend this life of mine?”

Is my son on to something here? I can’t help thinking of Buddhist scholar Howard Thurman’s advice: “Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

For me, homeschooling has required the patience to trust that letting my kids pursue what makes them feel most alive may not always feel like enough, but it may be just the thing they really need.

Book Review: Blood Brother: Jonathan Daniels and His Sacrifice for Civil Rights

This biography offers a fascinating new perspective on the civil rights movement and also provides a timely example of how white people can be effective allies to leaders of color working for change.

Blood Brother: Jonathan Daniels and His Sacrifice for Civil Rights by Rich Wallace and Sandra Neil Wallace

Blood Brother: Jonathan Daniels and His Sacrifice for Civil Rights by Rich Wallace and Sandra Neil Wallace (published by Calkins Creek) tells the true, meticulously researched story of a white Episcopalian seminary student who traveled from New England to Alabama in 1965 to work beside black people fighting for their voting rights. His story, probably best suited for ages 12 and up, offers a fascinating new perspective on the civil rights movement and also provides a timely example of how white people can be effective allies to leaders of color working for change.

Husband-and-wife writing team Rich Wallace and Sandra Neil Wallace were inspired to write Blood Brother after seeing Jonathan Daniels’s name popping up all over the place in Keene, New Hampshire, a small college town where they relocated several years ago. “Who was this local hero?” they asked themselves. After researching him a bit, their question became, “Why have we never heard of him? This is a national hero.”

They set out to tell his story and fill in some of the gaps along the way, and they’ve done a magnificent job. Because Daniels’s story was so little-known outside Keene, they often had to do a fair amount of detective work to piece together their narrative. For instance, they traveled to Alabama and used Daniels’s old photos of previously unidentified black activists to track down people who’d worked with Daniels and interview them. In some cases, this was the first time these civil rights veterans had gotten to tell their stories.

In another case, the Wallaces used facial forensic analysis to confirm that a photo of a man in a clerical collar at the 1963 March on Washington really was Jonathan. When the previously undiscovered photo first came to light in 2013, some of Daniels’s friends insisted it couldn’t possibly be Jonathan shown in the photo, because he’d never mentioned attending the March to his family or friends in Keene and also because the man in the photo was wearing a clerical collar, something Daniels wasn’t yet authorized to do in 1963. Other people swore the photo definitely showed Jonathan. The Wallaces’ detective work helped solve the mystery once and for all.

I was initially skeptical of this book when I saw it on the shelf. I feared that focusing on a white person who worked for civil rights would detract from centering on black people’s leadership and sacrifice. Too often, we’ve seen books and Hollywood movies portray the civil rights movement as being driven by noble white heroes, significantly muddying the truth.

The Wallaces definitely don’t fall into that trap in this book. Using Daniels’s story, they offer a valuable perspective on such black leaders as Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King, Jr. Their on-the-ground narrative shows very effectively how messy and disorganized the civil rights movement of the Sixties could sometimes be, and how its leaders and workers often disagreed among themselves about philosophy and practices. I think this is an important antidote to the rosy, idealized picture we’re sometimes presented of earlier civil rights movements, helping give this generation of activists a more realistic picture of how messy and confusing activism often is.

The book also offers a model of how white people can best help black people in their fight for justice. I was particularly moved by a moment in the book when Daniels went to a small town in Alabama to support high-school students organizing a protest of the denial of voting rights to their parents and the atrocious condition of their schools. The students looked to Daniels for advice, and it would have been easy for Daniels, an older, college-educated white man from a fairly privileged background, to play the authority figure. Instead, he told them this was their protest and that he was willing to help them do what they thought best. That kind of trust in black leadership and youth leadership is all too rare, even today.

That’s not to say that Daniels comes off as perfect or saintly. At times, he took actions that will provide readers with ample food for discussion about whether he did the right thing or not. But no matter what they think of some of his individual actions, I believe readers can’t help coming away from this book with a sense that Jonathan Daniels’s life definitely made a difference.

“See, Jon went beyond civil rights,” Stokely Carmichael once said of Daniels. “He went to man’s inhumanity to man, stripped of color.”

Civil rights leader and current United States Representative John Lewis praised Daniels this way: “I’ve heard of the work of Jonathan Daniels. Nitty gritty, dirty work. It was not flashy. . . but it was work that needed to be done.”

All these years later, there’s plenty of nitty gritty work that still needs doing. This highly readable, absorbing book provides bracing inspiration for that work.

Reflections on Mentorship (with a Little Help from Harry Potter)

When I was young, I benefited from the encouragement of some really wonderful mentors. They helped me see possibilities that I didn’t know were there. They were the models I emulated as I tried to figure out who I wanted to be.

They were also human beings with their own prejudices and weak points, just like anyone. Looking back, I can see that in my eagerness to please my mentors, I often forgot that they might not know everything, or that their advice might not be a perfect fit for me.

As my kids hit their tween and teen years, I find myself thinking a lot about how to help them get the most out of working with the mentors in their lives. How can I help them sift through mentors’ advice to find what’s relevant to them? How can I help them remember that mentors make mistakes and shouldn’t be treated as infallible oracles?

I mentioned my train of thought to a friend, and he mused that the Harry Potter series offers great examples of the good, the bad, and the ugly when it comes to mentors.

I loved the idea of exploring mentoring through the lens of Harry Potter, so I came up with a few Potter-infused principles of mentorship that I hope I can pass on to my kids:

- Good mentors admit their own biases and areas of ignorance. I want to encourage my kids to be skeptical of authority figures who offer up blanket advice and who assume that their advice will always apply to everyone. Good mentors will hedge their advice with phrases like “This is what worked for me” and admit their mistakes and the things they don’t know or understand. The best mentors (think Albus Dumbledore and Remus Lupin) have a sense of humor about themselves. They’re open to the possibility that they might not know everything and are willing to listen to a young person’s ideas and approaches, too.

- Good mentors ask the people they’re mentoring about their goals, hopes, and dreams and help their mentees to work toward those goals. Harry’s career counseling session with Minerva McGonagall in Order of the Phoenix is a good example. McGonagall took Harry seriously when he said he wanted to be an Auror, and she told him exactly what classes and grades he’d need in order to accomplish that goal. She saw him as someone worthy and able to do what he set out to do and offered him the tools he needed to get where he wanted to go. Of course, it worked in Harry’s favor that McGonagall was trying to score a point off Dolores Umbridge—yep, mentors are human, all right.

- Good mentors understand that their mentees aren’t simply younger versions of themselves. Remember Sirius Black and the way he sometimes confused Harry with himself and Harry’s father when they were teens? These kinds of mentors make the mistake of assuming that their mentees want exactly the same things that the mentor wanted at that age—or they assume that their vision of a young person is the only or best option for that young person without really seeing the young person for the separate, unique person they are. I hope my children will know it’s OK to speak up about what they hope to accomplish and to say no to serving as a mentor’s mini-me.

- Good mentors encourage their mentees to dream big dreams, but they also help them set realistic, do-able goals along the way. Ideally, mentors will encourage kids to shoot for amazing things, but they’ll also help lay out small, specific steps young people can take to move toward those goals. I’m thinking, for instance, of the careful, gradual way Dumbledore shared information with Harry about Voldemort’s horcruxes, letting Harry process things bit by bit rather than overwhelming Harry with too much information at once. Another example of the kind of mentoring I’m thinking of is the gentle, encouraging way that Remus Lupin helped Harry master summoning a patronus over several sessions. What a contrast to the way Severus Snape threw Harry into learning the difficult, scary work of occlumency without offering the slightest hint of kindness or emotional support! I want my kids to know that if they feel confused, overwhelmed, or stymied by advice their mentors give them, that it’s all right to ask for help breaking down big goals into smaller components, and that there’s no shame in asking for more directions along the way.

- Good mentors don’t play favorites or encourage cliques—or if they do, we mentees don’t have to let it distract us from our own intentions and purpose. We’ve probably all encountered the Horace Slughorns of the mentoring world at some point—the teachers, coaches, or bosses who cultivate an in-crowd of followers. If you’ve been invited to be part of an in-crowd, you know it can be flattering, but that it can also inhibit your ability to think clearly about what you really want and who you want to be apart from the group. On the other hand, if you’re not part of the in-crowd surrounding a coveted mentor, it can make you doubt your abilities and feel like a loser. I want my kids to be on the alert for either situation and to know that sadly, sometimes mentors use kids to feed their own egos. If my kids ever happen to be among the chosen few, I want to encourage them to resist the lures of an in-crowd and work toward staying true to themselves. And if they’re not tapped for the inner circle, I hope they’ll recognize that that doesn’t mean they’re destined for failure.

- Mentors aren’t always what they seem. In the fourth book of the Harry Potter series, Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher Mad-Eye Moody isn’t the person he appears to be, to put it mildly. I want my kids to know that it’s OK to trust their intuitions if they’re getting bad vibes from an authority figure. Often, really manipulative authority figures will do their best to turn kids’ intuitions against them; I want my kids to follow their gut when they sense that an authority figure may not have their best interests at heart or is not being honest about their intentions.

- Last but not least, good mentors deserve our gratitude and appreciation. I think as a young person, I didn’t always fully appreciate the extra time and attention that mentors were giving me (I’m still working on making sure I properly acknowledge my mentors’ kindness now that I’m an adult). As a kid, I didn’t realize just how busy adults were and what a gift it was when they were willing to offer me something extra to help me grow. I try to encourage my kids to show appreciation for their mentors, whether it’s writing a note after a teacher has been especially helpful or just saying, “Thanks! That was a great class!” as they walk out the door. I’m not asking them to name their kids after their most admired mentors the way Harry and Ginny do in Deathly Hallows, but I do want them to let their mentors know that their mentoring efforts mean something.

We adults talk a lot about the value of mentors, but I don’t think we coach kids as much as we should on the art of being coached. Equipped with this kind of knowledge, hopefully they’ll be better prepared to survive the Slughorns and Snapes of this world and to make the most of the Lupins and Dumbledores.

Because Homeschool Parents Need Field Trips, Too: My Artist’s Date to A Kid Lit Writing Conference

In her 1992 book The Artist’s Way, author Julia Cameron touts the creative benefits of regular “artist’s dates” to feed your spirit and spark your imagination. In late July, I took a doozy of an artist’s date and headed to the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators’ annual summer conference, held this year at the historic Millennium Biltmore Hotel in downtown L.A.

The Society, known by the acronym SCBWI, is one of the most amazing resources out there for people who write books for children (I joined SCBWI not long after beginning a nonfiction book about Charlie Chaplin for teens back in late 2012). Among many other helpful services, SCBWI sponsors two big annual conferences in New York and L.A. which draw children’s book writers, editors, agents, art directors, and illustrators from across the country.

Knowing that we homeschoolers are a book-loving bunch, I thought it might be fun to share some of the insights and inspiration I gleaned at the conference—and to give you a preview of some forthcoming books I heard mentioned there.

Pam Munoz Ryan, author of Esperanza Rising, was one of the conference’s first keynote speakers. She noted that interviewers sometimes ask her what she wishes people would ask her more often.

“I wish they’d ask me about failure as much as they ask me about getting an agent,” she admitted with a wry smile. She spoke of how often she finds herself thinking she’s on the right track with a book, only to discover she’s not.

“If you are not struggling,” she urged attendees, “if nothing is a challenge. . . then you’re setting your goals too low.”

In another keynote, publisher and editor Justin Chanda spoke of how important it was not to get caught up in writing to trends, telling the audience, “Erase ‘trend’ from your thinking. . . By the time you finish your manuscript, a new trend might be starting.” Instead, he encouraged writers to focus on writing the stories close to their hearts and telling those stories in the distinctive ways that only they can tell them.

Illustrator John Parra echoed Chanda’s sentiments in a later panel, telling the audience, “You don’t want to be a second-rate someone else. You want to be a first-rate you.”

Chanda also addressed the subject of diversity in children’s literature.

“Diversity is not a trend. Diversity is not the new vampires. Diversity is real life,” he asserted. He added, “Celebrating diversity. . . needs to be the norm.” Chanda is definitely practicing what he preaches: he recently launched Salaam Reads, a Simon and Schuster imprint devoted to depicting nuanced, realistic Muslim characters and themes.

For me, one of the must-attend panels at the conference was a presentation on Nonfiction/Fiction Mash-Ups by writers Elizabeth Partridge, Linda Sue Park, and Susan Campbell Bartoletti and agent Steven Malk. As the presenters shared their perspectives on when nonfiction veers into the realm of fiction, I found myself challenged to look harder at my own nonfiction project to make sure it really is just the facts, ma’am.

Linda Sue Park shared a particularly thought-provoking point about nonfiction, noting that almost all nonfiction eventually loses authority over time because of new research and new interpretations of the truth. Nonetheless, she said, it’s still important for writers to attempt nonfiction so that new information and perspectives can be discovered—even as nonfiction writers have to understand that they’re doomed to be found inaccurate on some points eventually.

Park also mentioned Fatal Throne, an intriguing new collaborative novel about Henry VIII and his six wives helmed by award-winning writer Candace Fleming. The novel will feature history-based stories from the point-of-view of Henry VIII and his wives, written by such noted authors as M. T. Anderson, Deborah Hopkinson, and Park herself. It’s due in Fall 2017.

At another break-out session, author Bonnie Bader offered tips for writing engaging biographies. Bader knows what she’s talking about—she’s written several biographies in Penguin Random House’s popular Who Was. . .? series (your kids might know them as “The Big Head Books”). Among her pointers: Try focusing on one particularly illuminating part of a person’s story instead of trying to cover a person’s entire life. She cited Martha Brenner’s Abe Lincoln’s Hat as a model of that approach. She also encouraged writers to steer clear of beginning biographies with the person’s birth, but to instead draw readers in with an attention-getting anecdote. As an example, she read the opening of her forthcoming biography Who Was Jacqueline Kennedy?, which showed Jackie taking Paris by storm in 1961.

For me, one of the most encouraging parts of the conference was hearing celebrated writers and illustrators admit just how humbling this business can be. Carole Boston Weatherford, the author of Moses: The Story of Harriet Tubman and Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-Ins, noted that when writers are first starting out, people always ask, “Have you published anything?” Once a writer has been published, she laughed, the question becomes, “Have you published anything I would have heard of?”

Author-illustrator Sophie Blackall also emphasized the humbling nature of publishing: “I don’t know anyone in this industry who says, ‘Oh, I’ve totally got this now.’”

Repeatedly, I heard from authors I admire that no matter how far you advance, you are still going to experience setbacks and self-doubt. But if you commit to the work and persist, you can find joy and growth through the struggles. Good advice for writing—and life.

Another conference highlight for me was meeting fellow nonfiction writer (and longtime homeschooling parent) Sarah Jane Marsh, whose debut picture book Thomas Paine and The Dangerous Word is due out in 2017. Sarah was incredibly generous about sharing what she wished she would have known when she was at the career stage that I am now. My takeaway? If I’m lucky enough to land a book deal, I shouldn’t be afraid to ask my agent and my editor questions and bring up concerns, even if I feel a bit awkward about it.

One of the last presentations I saw was by author Margarita Engle, whose memoir-in-poems Enchanted Air has been winning awards and rave reviews this year. In her book, Engle writes of feeling torn between her childhood in Los Angeles and her summers in Cuba with her mother’s family. Her inner conflict was heightened by the Communist revolution in Cuba, the Cuban missile crisis, and the eventual ban on travel to Cuba, a ban that created a painful divide between Engle and the family and the island she loved.

Engle noted that she consciously used present tense for Enchanted Air because she didn’t want her memoir to come across to kids as an old person’s reminiscences, as she self-deprecatingly put it.

“I wanted to take a young reader on a time traveling experience,” she explained.

She pointed out that her memoir came out not long after Jacqueline Woodson’s acclaimed 2014 memoir-in-poems Brown Girl Dreaming, also written in present tense and also showing a girl grappling with the intersection between the personal and the political.

“Maybe it’s a point in history where poetry is needed,” Engle mused.

This point in history often feels frighteningly tumultuous, especially with the current Presidential race stirring up so much discord. The writers, artists, and editors speaking at this year’s SCBWI conference couldn’t help acknowledging some of the difficulties our country is facing. But again and again, the conference’s speakers emphasized the power of stories to spread hope and change kids’ lives for the better.

As author-illustrator Drew Daywalt said in a Tweet sent from the conference, “Dear hurting America, take heart. Even as we struggle, know the people making stories for our children are some of the kindest people alive.”

After hanging out with some of those people all weekend, that was definitely my takeaway, too.

For more information on the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, visit the SCBWI website at www.scbwi.org.

The Life-Changing Magic of Embracing My Kids’ Reading Choices

My ten-year-old daughter plucked the book off the library shelf because she liked the look of it. It had a hot-pink spine, a cover photo of a girl’s arms protectively clutching a stack of notebooks to her chest, and a catchy title: Jessica Darling’s IT LIST: THE (totally not) GUARANTEED GUIDE to POPULARITY, PRETTINESS & PERFECTION.

“Oh, ick” was my first response, though I kept my opinion to myself. Don’t girls get enough pressure to obsess about their appearances and social status? I silently groused. Do they have to be pelted with it in books, too?

As strong as my feelings were, I managed to stay off my soapbox and keep my mouth shut. I remember all too well the day my sophomore English teacher noticed me reading Flowers in the Attic. My teacher had always supported and encouraged my love of writing and my insatiable reading habit. But at the sight of V. C. Andrews’ notorious novel in my hands, she sighed, “Oh, you shouldn’t be reading garbage like that. It won’t do your writing any favors, reading something so poorly written.”

I know she meant well, but I felt mortified—caught in the act of gobbling down the literary equivalent of Ho-Hos cupcakes. That feeling of shame stuck with me a long time (though it didn’t stop me from sneak-reading the rest of the series). In that moment was born a vow: if I ever had kids, I wouldn’t shame them for what they liked to read.

Throughout my kids’ early years, we hauled a little red wagon down the block to our local library just about every week and came back loaded with books for what we called “reading jamborees”—us snuggled up on our cat-clawed beige couch with a teetering stack of picture books and comics collections. Our reading jamborees ranged from Greek mythology and modern classics like the Frog and Toad books to Garfield comics. We were indiscriminate and voracious, devouring gorgeous, artfully crafted picture books alongside merchandising tie-in books starring Dora the Explorer, Thomas the Tank Engine, and Barbie, reveling in all of it—no judgment. No shame.

“If I dismiss a book they love as trash, I suspect it’ll make them less likely to share with me about other things they love. ”

Now that my daughter is ten and my son is thirteen, I’ve continued to follow a “no-judgment” policy when it comes to what they read (though I do tend to ask them to wait if a book seems too violent or sexy for their maturity level). I really can’t know how much my kids love or value a certain book, how much of their own emerging identity is connected to what they feel about a particular book. If I dismiss a book they love as trash, I suspect it’ll make them less likely to share with me about other things they love.